Puttable bonds are often described as the mirror image of callable bonds: equal in theory, opposite in structure. Yet in modern capital markets, put bonds have quietly vanished. This blog explores the reason behind that disappearance, arguing that it stems not from mispricing but from structural misalignment. Investors hold the right to exit, but lack the power to influence outcomes, leading to a contract with symbolic protection and no strategic value.

In this blog, I introduce the concepts of the Perception Gap and Power Asymmetry to explain why the put bond failed in practice. The lesson is clear: in finance, options only matter when the holder has control. Rights without power do not survive, and the market has already rendered its silent verdict.

When Financial Theory Meets Market Reality

In financial theory, symmetry is everything. For every call, a put. For every risk, a hedge. But the market doesn’t play by that symmetry. The call survives while the put disappears.

This blog is not about the pricing formulas. They work. It’s about the deeper truth the market quietly reveals: the put bond failed not because it was mispriced, but because it offered rights without power. Investors were given an option they couldn’t enforce. Issuers were asked to pay for a feature they couldn’t control. The result? A contract that looks perfect on paper, but never found traction in practice. Theoretical symmetry.

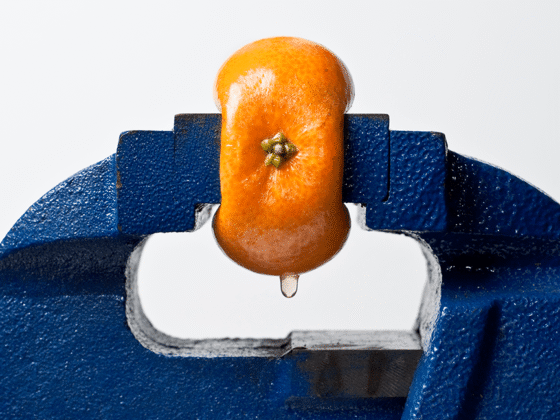

In the academic world, puttable and callable bonds are seen as elegant opposites. A callable bond is a straight bond minus a call option held by the issuer. A puttable bond is a straight bond plus a put option held by the investor. The symmetry. But giving investors a put option without control over the firm’s risk, leverage, or asset mix is like giving someone a parachute without a ripcord.

Markets are not rejecting math. They’re rejecting a contract that fails the power test.

The Perception Gap and Power Asymmetry

If the call survives and the put disappears, the natural question is why. The pricing models don’t fail. The structures are sound. And in theory, the put offers value. But the market has rejected it anyway. This isn’t an inefficiency. It’s a lesson in control.

Two forces drive the rejection: the Perception Gap and Power Asymmetry.

The Perception Gap begins with trust, or the lack of it. Investors may hold the contractual right to sell the bond back to the issuer, but they don’t control what happens before that day comes. They don’t control leverage, asset sales, payout policy, or management risk. They don’t sit on the board. They don’t see behind the curtain. So even if the issuer appears healthy now, the investor must price the put as if things could deteriorate without warning and without recourse.

From the issuer’s perspective, this creates a distorted cost. They’re being asked to insure against a pessimistic view they don’t share. The issuer may see the firm as stable, with no plans to increase risk. But the investor, lacking transparency, demands a premium for the unknown. The put option becomes expensive—not because of volatility, but because of mistrust.

And deeper still is the Power Asymmetry.

The call option held by an issuer is a tool. It allows for refinancing, redemption, strategic timing. It lives in the hands of the party that controls the asset. But the put? It offers no such leverage. The investor may “exit” the bond, but that exit doesn’t change the company’s behavior, structure, or value. The option to walk away is different from the power to act.

In practice, this means the put is hollow. It lacks teeth. It offers a theoretical exit, not strategic influence. And because it resides with the weaker party — the one without visibility or control — it becomes a symbolic right, not a functional one.

A Silent Verdict from the Market

That’s why the put doesn’t trade. That’s why it doesn’t appear in portfolios. t’s about authority. The investor has a right but no power.

The most powerful evidence against the put bond isn’t found in pricing spreads or volatility models. It’s found in what’s missing. There is no market.

Puttable bonds are rarely issued, barely traded, and almost absent from portfolios –confirming their disappearance. This isn’t a failure of awareness. Investors know what a put does. Issuers can structure it easily. If the market believed the instrument had value, it would be everywhere. But it isn’t.

Because markets, unlike models, have memory. They’ve seen how put bonds behave in the real world. Investors don’t trust that the option will matter when it’s needed most. Issuers don’t see the feature as worth its cost. Liquidity providers don’t want to hold something that might vanish when things get difficult.

So the market moved on – quietly, without protest, without needing a correction.

The silence isn’t apathy. It’s judgment.

It tells us the models were too clean. The assumptions too optimistic. The contract too abstract. And it reminds us that financial products only survive when they serve real behavior, not just theoretical symmetry. Build structures that align with control, visibility, and action.

Finance isn’t just about cash flows and optionality. It’s about who controls the narrative when things go wrong. That’s where value and survival are found.

Rights Without Power

Put bonds didn’t vanish because of faulty models. They vanished because the real world exposed their flaw. In theory, they offered investors control. In practice, they offered a one-time exit without any ability to shape outcomes. That disconnect between ownership and authority turned the put from a hedge into a hollow feature.

The lesson is broader than just this instrument. In finance, as in law and governance, contracts only work when control matches optionality. Markets will not support structures that look fair but function weakly. The put bond failed not due to mispricing, but due to misalignment.

And that is why the absence of put bonds is not a market failure. It is a market decision. A contract with no teeth, no control, and no future was quietly retired, without noise, without protest, and with perfect logic.