The opening hours of Hell Is Us are brilliantly confusing. The game tasks you with getting up to speed on a complicated civil war between the Palomists and Sabinians. A deluge of proper nouns is unleashed: Lymbic weaponry, Guardian Detectors, and more. But the clearest way the game communicates that you should feel utterly dumbfounded is through the cryptic stone panels scattered amid its ravaged, Eastern Europe-coded setting; you’re unable to actually read the text engraved in these tablets. At every turn in the first levels — a dank forest and then a fetid bog — meaning and, just as importantly, understanding, eludes.

In this manner of willful bewilderment, Hell Is Us evokes Hidetaka Miyazaki’s constellation of soulsborne hits. Like those games, notably Elden Ring, here beckons a world of esoteric symbols, puzzles, and inscrutably complex history. Combat also apes the cadence of quintessential Miyazaki titles: stamina drains with each thunderous strike, recuperating only in moments of panicked or planned retreat.

Yet that’s where the FromSoftware comparisons end. Hell Is Us is also a detective game: you are given a pleasingly chunky retrofuturistic datapad in which you store a small encyclopedia’s worth of information, and there are spider diagrams filled with leads to follow. To solve the game’s more devilish conundrums, you may wish to have a pen and paper on hand!

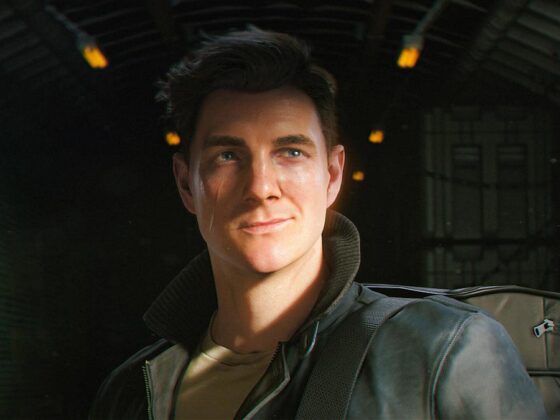

Befitting both its own name and game title, the fictional country of Hadea has fallen into war-torn carnage — in essence, becoming hell itself. The first hour shows the grisly aftermath of a firing squad and lynched bodies swinging from a tree. Nearby, a soldier plays a maudlin tune on a violin. Bizarre white creatures stalk marshes and blustery plains; gigantic orbs barbed with spikes — so-called Time Loops — pulsate. These anomalous fissures in time and space are the result of the so-called “Calamity,” and it is up to protagonist Rémi, a gorpcore investigator-cum-action-hero, to send them back to oblivion.

At first, the game seems like a hodgepodge of visual styles: bleak landscapes, mannequin-like creatures, technical wear fashion, gigantic swords to rival Cloud Strife’s in Final Fantasy VII. Slowly, it begins to coalesce, taking on a sublime, haunted quality suffused with dream logic. The strangeness is compounded by the sheer density of obscure puzzles. What maddening realm is home to so many arcane riddles?!

There is a lot to process in Hell Is Us. This extends to its enemies who, if especially powerful, summon support beings via a weird, metaphysical umbilical cord. One is a white, humanoid creature; the other is a brightly colored, geometric foe. There’s a further wrinkle, as each color corresponds to an emotion: blue for grief, green for terror, and so on. The metaphor is a little hackneyed yet potent. These enemies are physical manifestations of war’s emotional wreckage. They wander the landscape, imbuing it with a surreal, psychic quality. But the symbolism is a little limited: how do you put an end to intergenerational grief? According to Hell Is Us, by cleaving it in two using hand axes infused with rage.

There is a breadth of ambition and imagination here but uneven execution. Take our hero, who looks great in his flapping, rain-resistant poncho, yet speaks like a gruffer, more cynical version of countless male game protagonists from the late 2000s. Gazing upon a cathedral-sized mound of human bones, Rémi (played by Elias Toufexis, aka Adam Jensen from the Deus Ex series) muses aloud: the Sabinians may be the victims here but the region is also littered with Palomist graves. It is an odd, jarring line, to make this kind of equivalence when confronted with such monumental loss.

After the wonderfully discombobulating opening hours, Hell Is Us loses some momentum. Hadea remains a beguiling setting throughout; the desire to pull at its various laced mysteries never wanes. But the same can’t be said of the other narrative layers, either Rémi’s own personal voyage to discover the fate of his parents and the place he fled as a young child, or precisely what the Calamity is. The former is intended to propel the player’s exploration yet it does not grip. Without the requisite narrative intrigue, the plot boils down unlocking a series of doors decorated with ornate glyphs. At one point, a character inadvertently sums up the prosaic plot: “So you found a door with a strange mechanism. What happened next?”

Meanwhile, combat — which is an activity you need to do a lot of in order to decipher the weird event that caused the appearance of the unnerving pallid creatures — becomes rote. My attention started to dwindle around hour 15 of a possible 30.

This is a shame because Hell Is Us does so much that is admirable and interesting. The actual dungeons that plummet below the game’s semi-open zones are a spatial symphony of claustrophobic passageways and soaring, light-filled atriums and altars. There are no waypoints or quest markers; you must carefully read journals for navigational clues (and sometimes use a compass). Another smart design choice: you can only talk to characters about information you have already uncovered. In this era of often anodyne and frictionless big-budget video games, where anything that might potentially limit a game’s audience is carefully considered and often avoided, it is refreshing to play something that is so intentionally prickly.

As I trudge forward in this muddy, miserable land, my mind keeps circling back to language and understanding: the codes, symbols, tongues, and customs of Hadea. It’s clear that I am only grasping a tiny fraction of this millennia-old conflict. But there is another, more universal language that the game seems to use, which it relays through bracing imagery: the misery of war.

Regardless of time and place, violent conflict breaks people in much the same way, making them scared, angry, vengeful, and, naturally, violent. Despite its myriad of shortcomings and sheer informational density, Hell Is Us speaks with clarity: of war, it is impossible to close Pandora’s box once its evils have escaped.

Hell Is Us launches on September 4th on the PS5, Xbox, and PC.