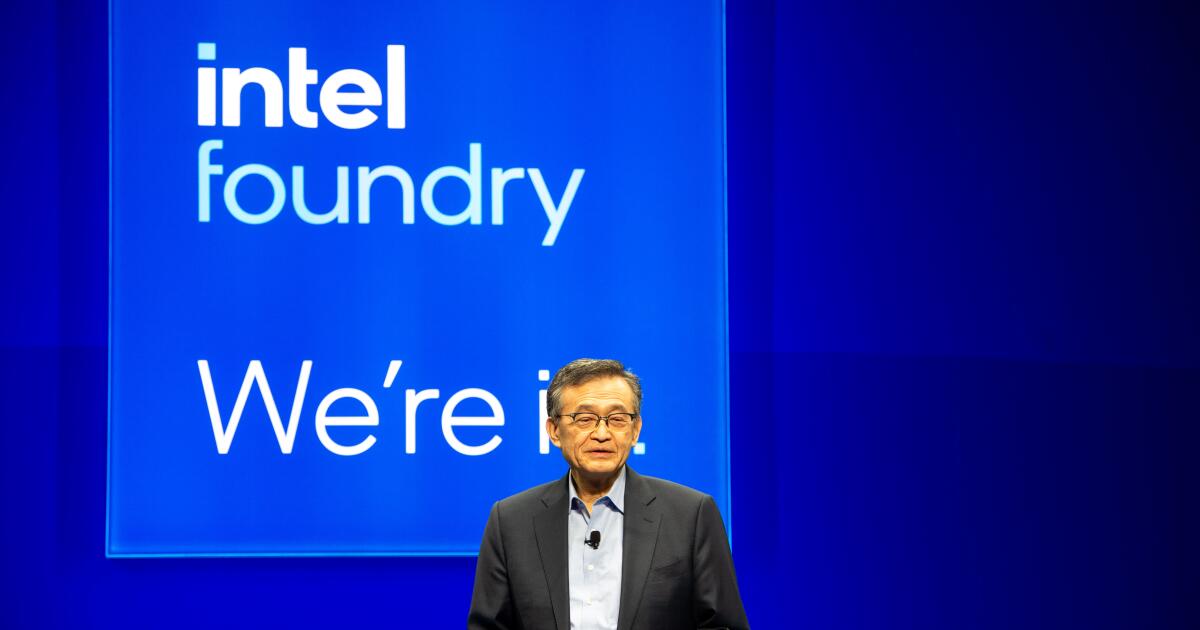

Earlier this year, Intel’s new chief executive Lip-Bu Tan made frank remarks about how the Silicon Valley chipmaker keeps coming up short.

“For quite a long time for Intel, we fell behind on innovation. As a result, we have been too slow to adapt and to meet your needs,” Tan told Intel’s customers and partners at a company event in late March. “You deserve better, and we need to improve, and we will.”

Intel, a Santa Clara-based tech behemoth that fueled the rise of personal computers, sits at a major crossroads in the company’s 57-year-old history as the competition to dominate artificial intelligence escalates. Known for making the “brains” that power computers, Intel used to be the most valuable U.S. chipmaker before Nvidia claimed the top spot. It’s also facing more competition from rivals such as Advanced Micro Devices and Samsung.

The AI frenzy has greatly benefited Nvidia, a company that created a specialized computer chip that’s proven valuable not only for gaming but also for AI model training, data centers and robotics. While Nvidia’s worth ballooned to more than $4 trillion, Intel has seen its market value drop to around $87 billion.

“It’s going to be tough for them,” said Mario Morales, group vice president for enabling technologies and semiconductors at the International Data Corporation. “They missed a very big shift and they don’t yet have the products in AI to compete — and that market is growing fast.”

In the last five years, Intel’s stock price has plunged more than 58%. It posted a net loss of $18.8 billion in 2024 and plans to slash roughly 25,000 workers this year.

Intel’s lengthy history has been filled with highs and lows, but a series of big missed opportunities, manufacturing delays and management missteps hampered the growth of a company long synonymous with Silicon Valley’s rise, analysts say. Tan, a 65-year-old tech leader who became Intel’s chief executive in March, is trying to steer the company in the right direction.

Intel has bet big on its foundry business, taking on Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co., which makes chips for other companies such as Apple and Nvidia. Reining in costs, Intel has scrapped manufacturing projects in Germany and Poland while slowing construction of its Ohio factories.

“There are no more blank checks. Every investment must make economic sense,” Tan told employees in a memo last week.

Intel’s rise and fall

Founded in 1968, Intel focused heavily on researching and developing new technologies in its early days.

Robert Noyce and Gordon Moore, already well-known tech figures, left their jobs at Fairchild Semiconductor to launch what would become Intel. Noyce co-invented the integrated circuit, laying the foundation for the development of laptops, smartphones and other modern electronics. Moore was known for making an observation that became a guiding principle for the semiconductor industry.

The company grew rapidly in its early years. Intel’s first engineers worked from a conference room in Mountain View, Calif., before the company moved to its own facility in Santa Clara. The company released memory chips before creating the world’s first commercially available microprocessor and other innovations that made it possible for companies to build more affordable computers. As computer sales from Dell, Microsoft and other tech companies rose, Intel saw its market value reach a record $495 billion in 2000 during the dot-com boom, according to Reuters.

But the company also made a series of missteps that would haunt it later, analysts said. Intel declined to comment.

“It’s been on a weak footing for so long because of those historical poor decisions,” said Jacob Bourne, a technology analyst at eMarketer. “Now it’s at this point where it has to cut all these costs to try and become profitable.”

One of Intel’s biggest missed opportunities: supplying chips for the first iPhone in 2007.

Former Intel Chief Executive Paul Otellini told The Atlantic in 2013 that Apple was interested in paying a certain price for a chip but it was below what Intel forecasted. That prediction turned out to be wrong and Otellini expressed regret for not following his gut.

“We ended up not winning it — or passing on it, depending on how you want to view it. And the world would have been a lot different if we’d done it,” Otellini said in that interview.

But strategic missteps weren’t Intel’s only problems. The company experienced process technology delays, opening the door for its rivals such as AMD that offered powerful and efficient chips to capture customers.

Pat Gelsinger, who served as Intel’s chief technology officer before returning to lead the chipmaker in 2021, focused on an ambitious and costly turnaround plan for the company. He set a goal in which Intel would develop five new semiconductor process nodes within four years.

The federal government awarded Intel billions of dollars last year to support its semiconductor manufacturing expansion in the United States but the company’s net losses were also widening. In 2024, Intel’s foundry business reported an operating loss of $13.4 billion, nearly double compared with the previous year‘s loss, according to its annual report.

“Gelsinger threw fuel on the fire, because he started spending money like crazy to build out this massive amount of manufacturing capacity for business that they did not have,” said Stacy Rasgon, a senior analyst at Bernstein covering U.S. Semiconductors.

Then the board reportedly forced out Gelsinger, who announced his retirement last year before Tan took over as chief executive.

Another turnaround plan

Intel’s new chief executive has been focused on cutting costs including around the company’s foundry business. He told employees in a note last week the company invested too much money without enough demand.

And Intel said it might pause or discontinue its upcoming chip manufacturing process technology known as 14A if it can’t land a “significant” customer.

While Intel has been eclipsed by some of its rivals, the company is still a big player in the semiconductor industry.

IDC, which analyzed semiconductor revenue, said in 2024 Intel ranked third behind Nvidia and Samsung. It dropped to the fourth spot behind SK Hynix, a South Korean company that supplies memory chips, during the first quarter of this year.

Analysts don’t see Intel going away anytime soon. And as tech companies work on rolling out new AI-powered hardware, that could also present another opportunity for Intel.

Alvin Nguyen, a senior analyst at Forrester, said some of the concerns around Intel being in trouble might be “overstated.”

“They may not be at the top like they once were, but they are still, ultimately, very important for all industries because their chips are used virtually everywhere,” he said.